The words flout and flaunt are so often mixed up—or more precisely, flaunt is so often used where flout is meant—that they take first place in Merriam-Webster’s list of “Top 10 Pairs of Commonly Confused Words,” even ahead of the notorious rein/reign (another peeve).1

To flaunt (vt) means “to display ostentatiously or impudently,” as in this passage by the Argentine writer Hebe Uhart:

Families that come from the progressive tradition tend to have good taste. They do not flaunt their wealth; they tend to be discreet about the real estate they own, critique mindless spending because it’s unbecoming, and if they are professionals, let’s say doctors or dentists, they have paintings of horses galloping in the office, but it’s always a discreet gallop, nothing out of control.2

If you mean “to treat with contemptuous disregard,” the word you’re looking for is flout, as in this recent New York Times headline: “Chinese Traders and Moroccan Ports: How Russia Flouts Global Tech Bans.”

But let’s have a more colorful example. Here’s The Age of Innocence (1920), by Edith Wharton:

It was one of the misguided Medora’s many peculiarities to flout the unalterable rules that regulated American mourning, and when she stepped from the steamer her family were scandalized to see that the crape veil she wore for her own brother was seven inches shorter than those of her sisters-in-law, while little Ellen was in crimson merino and amber beads, like a gipsy foundling.

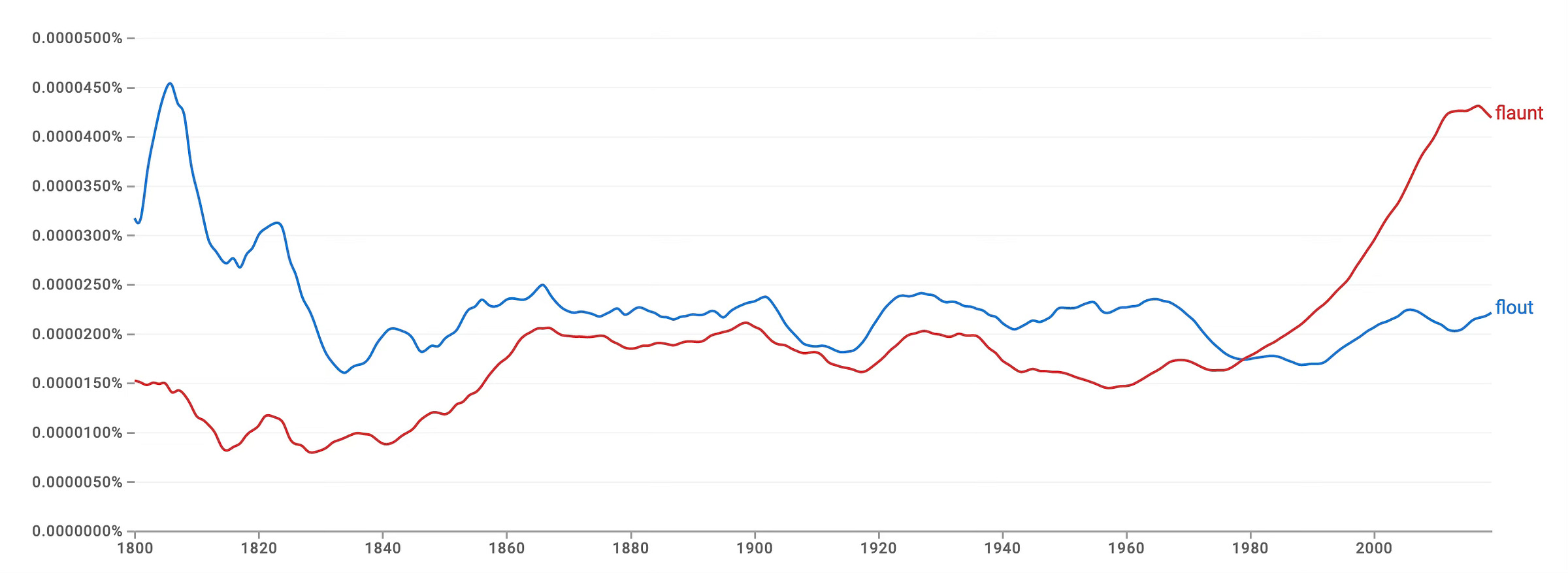

Flout and flaunt both entered the English language in the mid-16th century,3 and they seem to have coexisted harmoniously for hundreds of years.

Then, according to the Online Etymology Dictionary, something changed. While the intransitive sense of flaunt, meaning “to display oneself in flashy clothes,” dates from the 1560s, the transitive sense, to “flourish (something), show off, make an ostentatious or brazen display of,” doesn’t crop up until 1827.

Becoming a transitive verb put flaunt on even ground with flout, grammatically speaking. So it makes sense that the mixing up of these two words didn’t become an entrenched habit until the 20th century.

“Once the use of flaunt to mean ‘to treat contemptuously’ took off, it proved very difficult to convince people that they should not use the word in this fashion,” says Merriam-Webster, offering several examples of that wrong usage, including this one:

Instead of the rich whose opportunities are great setting examples of patriotism and fidelity to principle they flaunt the law and make it a jest.

—The Salt Lake Telegram, 18 Jan. 1905

Here’s a more modern illustration of the problem, from the Denver Post (with a dangling participle as a bonus):

Listening to each, neither bands [sic] sounds tied to any one sound over the course of an album. Instead, they flaunt convention—if an accordion sounds good in a song, they’ll throw it in.

It intrigues me that flaunt is used so often to mean flout, while the use of flout to mean flaunt is relatively rare. Merriam-Webster offers a single example (without a final period, for some reason):

“The proper pronunciation,” the blonde said, flouting her refined upbringing, “is pree feeks” — Mike Royko

Dictionaries are, of course, descriptive: “If enough people use a word in a certain fashion, we are compelled to record that use,” says Merriam-Webster. Because “flaunt with the meaning ‘to treat with contemptuous disregard’ is found in even polished, edited writing,” this source explains, “that meaning is included in dictionaries as an established use of the word.”

But dictionaries don’t have to like it.

The American Heritage Dictionary’s usage note about these two words warns:

For some time now flaunt has been used in the sense “to show contempt for,” even by educated users of English. But this usage is still widely seen as erroneous.

Merriam-Webster explicitly says about this usage of flaunt that “you may want to avoid it: there are still many who judge harshly those who (they feel) are flouting proper English usage.”

The dictionary’s blog expands on this point in a post rather oddly titled “‘Flaunt’ vs. ‘Flout’: Is it wrong to confuse these words?” (What a question!) With a heavy dose of attitude—not to mention a “this” without a clear referent—the article warns that

although we include the recent sense of flaunt, this does not mean that we are suggesting you use it in such a fashion, and most copy editors, usage guides, and grammatically inclined pickers of nits would judge you for doing so. Some of them might even snigger.

(Snigger? No. What a copyeditor would do, upon encountering a flaunt that should properly be a flout, is query the author about it.)

Way back in 2017, noting that BBC Radio 4 was leaving uncorrected the use of flaunt to mean flout in its parliamentary reports, Geoffrey K. Pullum on the Language Log blog concluded that “the flaunt/flout distinction may be a lost cause.”

I do hope not. But the more flaunt is allowed to encroach on flout’s territory, the closer flout approaches to extinction.

Words get mistaken for each other for all sorts of reasons. What made flout and flaunt especially vulnerable?

Although the “original senses” of the two words “are not synonymous,” says Merriam-Webster, they both “have connotations of disapproval, and each one describes an action that many people would find unseemly, or improper.”

Flout and flaunt have a stylistic similarity, a shared performative quality.

“The openness and arrogance of both flaunting and flouting have probably contributed to the confusion of the two,” says The Columbia Guide to Standard American English, “but Edited English still insists on the two verbs being distinguished.”4

Insists! So in support of Edited English (I like that classy capitalization), let’s have some more examples of correct usage.

Here’s Sadie Stein writing in the Paris Review:

In some ways, the sands of time were running out, and our glory days were behind us. Soon, behaviors we’d once been rewarded for would be recognized as obnoxious, or precious, or odd. We’d have to hide them rather than flaunt them.5

And here’s Rachel Carson:

We still talk in terms of “conquest”—whether it be of the insect world or of the mysterious world of space. We still have not become mature enough to see ourselves as a very tiny part of a vast and incredible universe, a universe that is distinguished above all else by a mysterious and wonderful unity that we flout at our peril.6

For more on rein/reign, as well as flush/flesh, palette/palate/pallet, and other irritating word confusions, see

’s excellent roundup of mistakes that set her teeth on edge.Hebe Uhart, “Inheritance,” Paris Review (blog), April 2, 2024.

Kenneth G. Wilson, The Columbia Guide to Standard American English (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), 197.

Sadie Stein, “Growing Pains,” Paris Review (blog), May 28, 2015.

Rachel Carson, “Of Man and the Stream of Time,” speech, Scripps College, Claremont, California, June 12, 1962, in Rachel Carson: Silent Spring & Other Writings on the Environment (Library of America, 2018), 423–24.

Thanks for the shout-out!