In copyediting, a query (short for author query) is a note to the manuscript’s author addressing a particular issue in the text. (Most writers are probably more familiar with the other kind of query—a pitch letter to an agent or editor.)1

A copyeditor can resolve most errors and inconsistencies (of grammar, style, punctuation, etc.) in a manuscript independently. But when an appropriate fix requires additional information, the copyeditor (CE) queries the author (AU).

These days, that means adding a comment in a Word file or Google Doc. In the old hard-copy days, it meant handwriting a note in the margin of the manuscript, usually in colored pencil. Whether electronic or handwritten, an author query should be concise and clear; the tone should be polite and professional.

As the reader’s representative and advocate, the copyeditor champions clarity, working to smooth out any bumps in the text so that the reader can easily follow the author’s meaning. At the same time, the copyeditor is a loyal ally to the author, paying closer attention to each word and sentence than most of the book’s readers ever will.

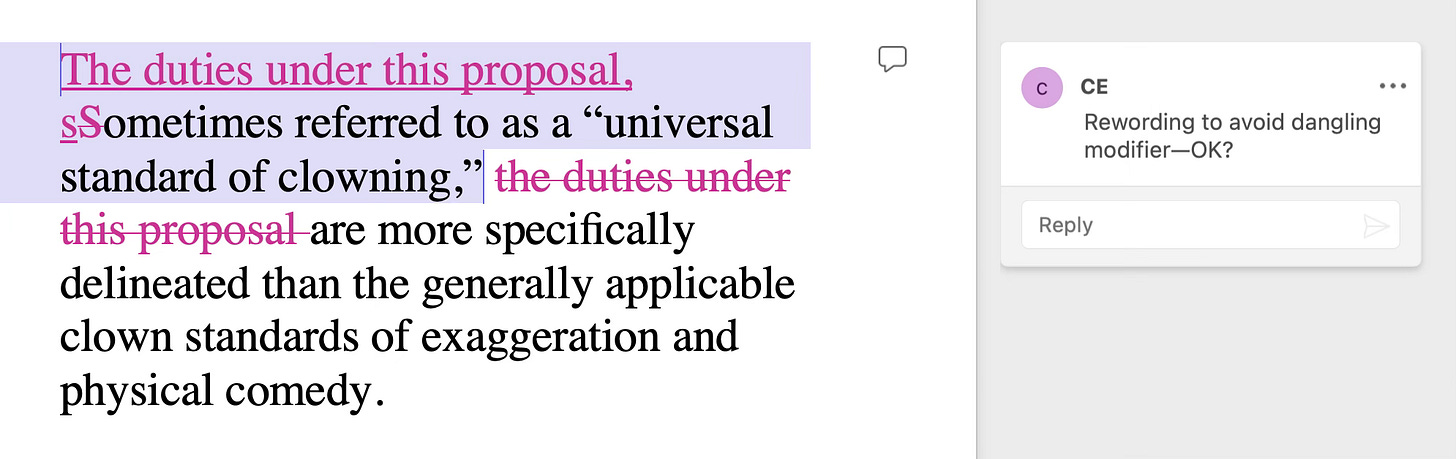

Often a query simply calls attention to a particular change, to make sure the author has considered and agreed to it. For example, if I changed an antiquated-looking “amongst” to “among,” I might ask, “OK?” just to be sure the author didn’t object.

Copyeditors don’t take lightly even the smallest rewording of the author’s original. As

says, the copyeditor’s job is not to rewrite the text but “to burnish and polish it and make it the best possible version of itself that it can be.”2If the reason for a particular change might not be immediately obvious, the copyeditor should explain briefly why the revised version is preferable. (Copyeditors have a reason for every change they make.) For example: “This 3rd occurrence of ‘scudding’ within a single chapter could be distracting: choose a different word here?”

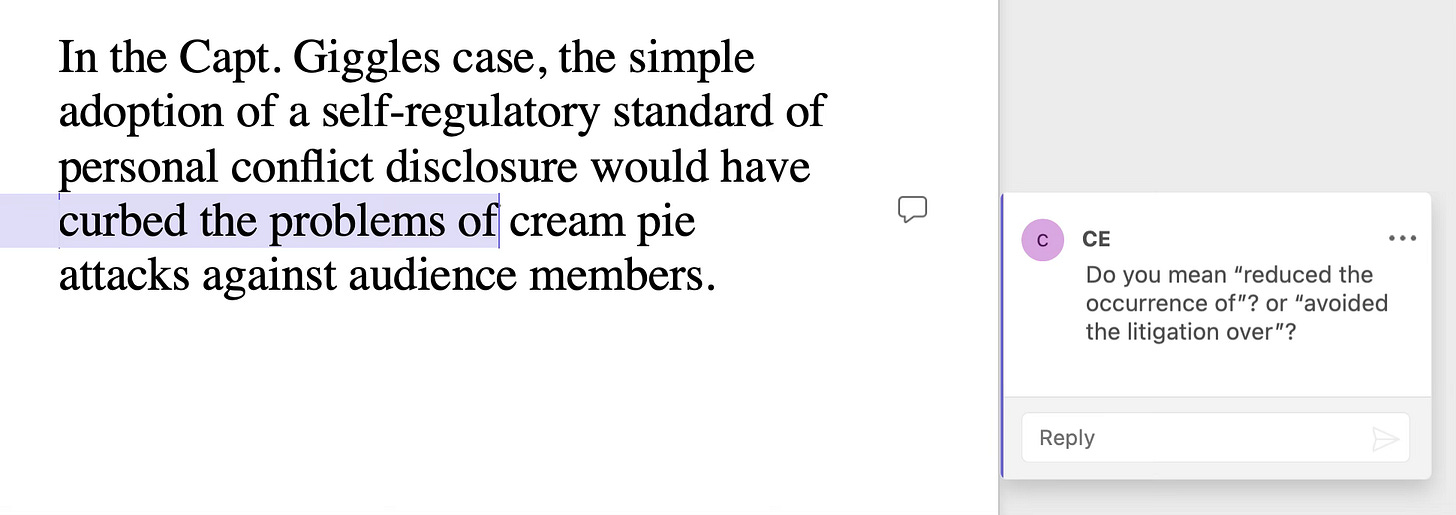

Even a straightforward correction of a grammatical error might warrant a query to explain exactly what was wrong with the original text. Many a legitimate correction has been rejected by the author because the copyeditor didn’t adequately explain the problem.

For example, if an author used “whomever” in a grammatical structure that called for “whoever,” it would behoove me to explain as well as correct the error. Otherwise, this writer (who initially thought “whomever” was correct) might simply disagree with my change and reject it.

Even when the reason for a particular change is the publisher’s preferred style, the copyeditor will typically give the author an opportunity to disagree. For example, I might change “healthcare” to “health care” and add the query, “Per house style—OK?” If the author has a reason not to follow the publisher’s style (or even the dictionary) on a particular point—conventions within the author’s field of study, for example, or a personal preference for British style—that exception is usually allowed, as long as it’s applied consistently throughout the manuscript.

Meatier queries ask the author to clarify an intended meaning—“By ‘a lower population’ do you mean ‘a smaller population’ or ‘a lower population growth rate’?”—or to choose among several proposed solutions to an issue.

Once the manuscript has been copyedited, it goes back to the author, who reviews all the proposed changes (accepting or rejecting each one) and responds to all the queries. The manuscript then returns to the copyeditor, who implements all the author’s decisions.

This back-and-forth between the copyeditor and the author is the last opportunity to correct any actual problems in the text or make any significant changes. (Ideally, the proofreading stage, which happens after the book has been typeset and laid out, is for catching new errors introduced during those later steps in the process.)

The dozens (or hundreds) of queries on a manuscript make up a long conversation between copyeditor and author about the text. Even when it’s all electronic, the conversation is a slow one. The copyeditor asks a lot of questions all at once and then waits. A few weeks later, the file returns with the author’s answers.

Back when the copyeditor’s queries and the author’s responses were written by hand in the margins of a paper manuscript, this conversation felt even more epistolary. With the physical manuscript trundling from one party to the other via UPS Ground, the delay between question and answer was a feature of the genre, a little like the wait between installments of a serial novel.

If you’re interested in the pitch kind of query, follow

, who teaches classes in query letter writing.Benjamin Dreyer, Dreyer’s English: An Utterly Correct Guide to Clarity and Style (New York: Random House, 2019), xi.

![Sentence: According to the pledge, Patches and Slappy would co-fund a poll that pitted each of them against Big Bozo in a two-clown race and agree that whomever [whoever] underperforms against him in the poll will drop out of the King Clown Contest. Query: Nominative case needed here because “whoever” is the subject of the verb “underperforms.” Sentence: According to the pledge, Patches and Slappy would co-fund a poll that pitted each of them against Big Bozo in a two-clown race and agree that whomever [whoever] underperforms against him in the poll will drop out of the King Clown Contest. Query: Nominative case needed here because “whoever” is the subject of the verb “underperforms.”](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!BPVT!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ffa3ab2dd-0e25-4496-9aa5-eba9d3db4a93.heic)

Thank you for the shout out about my class! I LOVE the Benjamin Dreyer book, as well.