The one thing everybody knows about worry is that it does no good. It’s useless, pointless, without effect. Like poetry, worry makes nothing happen.1 The expression “Don’t worry” is nearly as ubiquitous as “Have a nice day.”

And yet the worrier can’t just stop it. Worrying is a habit (like smoking?).

Or maybe it’s a talent. I myself excel at worrying. Some people juggle (having practiced for innumerable hours over many years); I worry (ditto).

Current events are adding daily to my personal catalog of worries, which was already extensive. I routinely worry about identity theft and bread mold and scoliosis and microplastics. I worry about feline hepatic lipidosis and bedbugs and whether I eat enough dark leafy greens. Now I also worry about a “forced cutover” of the country’s banking and telecommunications systems to an everything-app version of Xitter (on the model of China’s WeChat).2

In modern English, the noun worry is more or less synonymous with anxiety. But as someone who’s deeply familiar with both conditions, I’d say worry doesn’t get enough credit for being an activity. Worry is a practice, a pursuit. It requires energy. It burns calories. (It had better burn calories.)

Worry is a verb

The word itself is very old, as the poem “Worry,” by Nan Cohen, reminds us:

A thousand-year-old word is a nip

at the heel of the mind. …3

Worry started out as a (transitive) verb: it was wyrgan in Old English and meant “to strangle.” By 1300, according to the Online Etymology Dictionary, it had become the Middle English wirien, meaning “‘to slay, kill or injure by biting and shaking the throat’ (as a dog or wolf does).” It took only a hundred more years for the figurative sense “to annoy, bother, vex” to catch on (by 1400).

But it wasn’t until the 1820s that the verb added the meaning “to cause mental distress or trouble.” By 1860, it had gained an intransitive sense, “to feel anxiety or mental trouble.”

Over time, the “biting” aspect became increasingly figurative, going beyond “bothering” to include nibbling with the fingers instead of the teeth. Now the same verb that describes a terrier’s assault on a doomed rat can also mean merely “to touch or disturb something repeatedly” (sense 2c, according to Merriam-Webster). Hence (eventually) the fidget spinner.

Worrywart

It was common knowledge among my elementary school peers that someone who worries is called a “worrywart” because worrying causes warts. (It now strikes me as a miracle that my younger self did not immediately add this “fact” to my list of worries.)

A worrywart is indeed, says M-W, “a person who is inclined to worry unduly” or “without reasonable cause.” Synonyms include handwringer and nervous Nellie. (British English also has worryguts, as I learned from

’s indispensable Green’s Dictionary of Slang.)But in fact, “Worry Wart” was originally “a generic nickname or insult for any character who caused others to worry, which is the inverse of the current colloquial meaning,” says the Online Etymology Dictionary (emphasis added). The term first appeared in 1929 and is attributed to the newspaper comic “Out Our Way” by American cartoonist J.R. Williams (1888–1957):

For example, from the comic printed in the Los Angeles Record, Dec. 5, 1929: One kid scolds another for driving a screw with a hammer “You doggone worry wart! Poundin’ on a nut till it’s buried inta th’ table!”

Either way, the term is further evidence of the denigration of worry as silly or wrongheaded.

Worry beads

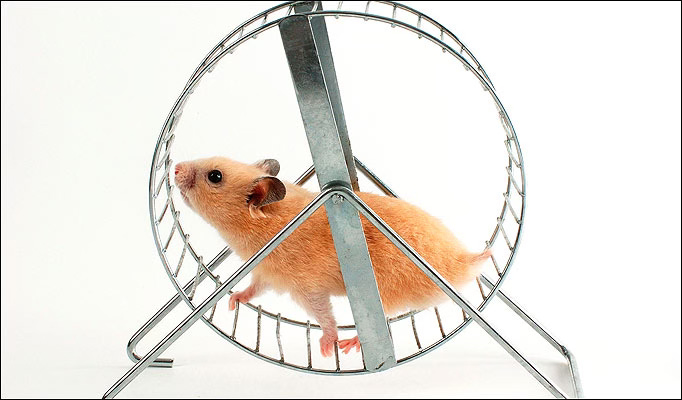

Being a worrywart myself, I sometimes envy people who grew up in a tradition that involves prayer. Prayer, as I understand it, is directed outward—toward an unseen listener or into the universe. Heathens like me have to make do with worry, which goes nowhere. If prayer flies like a dove, worry runs furiously in place like a hamster on a wheel.

But one thing prayer and worry have in common is beads.

Worry beads are “a string of beads that can be fingered to keep one’s hands occupied,” says M-W. Though the term didn’t enter the dictionary until the 1950s or 1960s, the beads themselves have a long history in multiple cultures, like the prayer beads (rosaries and the like) that they’re clearly related to. (The word bead comes from Middle English bede, meaning “a prayer.”)

The most familiar modern worry beads are those used in Greece, where they’re called komboloi (“bead collection”) and are often made of amber or coral (according to Wikipedia). The etiquette for using Greek worry beads encompasses both a quiet fingering method, for worrying in private settings, and a noisier method, presumably for public displays of anxiety.

Even quieter than worry beads is the fidget spinner.

Once a means of bloody, toothy murder, the act of worrying has been reduced to mere fidgeting—an undesirable, if benign, often unconscious behavior.

(I’ve never tried a fidget spinner myself. Or worry beads, for that matter. But I probably should. “It’s good to have something fiddly close at hand,” says novelist and admitted fidgeter

, who always has “a lot of magnets to play with.”)

Worry is a form of story

When faced with uncertainty—How will the interview go? Will our democracy survive? And what about Naomi??—we often resort to worry. The act of worrying gives us some imaginary control over a situation.

Which is to say our minds spin stories about uncertain outcomes, often tending toward worst-case scenarios—because, upsetting as the prospect of a bad outcome may be, it’s still less terrifying than an unknown one.

The human mind is obsessed with stories. It makes up stories all night, and as Jonathan Gottschall points out in The Storytelling Animal, “we don’t stop dreaming when we wake”: daydreaming is actually the waking mind’s default state. Researchers estimate that “the average daydream is about fourteen seconds long and that we have about two thousand of them per day.”4

Since daydreaming is a conscious activity, I assume that non-worry-prone people are free to imagine strolling on a pristine beach or winning the Pulitzer Prize.

But worriers daydream about disasters large and small. I worry about supervolcanoes and old electrical wiring and fire ants and whether the driver behind me is going to look up from his phone in time to notice that we’re coming to a red light.

But for writers (who are notorious worriers), “worry is not all bad,” says

. Worrying about the workings of a piece of writing is part of the process, and according to Saunders, “if we turn to our fears with all our creative energy, there is less chance they will come true.”So: we admit a fear (and that feels good, and honest) and then resolve to face that fear. Facing that fear is exactly equal to craft. And this then clears the way for some specific, technical work. Our worry is no longer psychological or abstract. …

Writers have something better than a plastic fidget spinner. “In writing,” says Saunders, “the most powerful antidote we have for worry is: revision.”

Yes, W.H. Auden did indeed say (in a poem), “Poetry makes nothing happen.” But has there ever been a clause more often taken out of context and deliberately misunderstood? For an efficient discussion of this matter (which has more relevance to our current moment than you might expect), see Don Share’s 2009 essay “Poetry makes nothing happen … or does it?”

Nan Cohen, Thousand-Year-Old Words (Glass Lyre Press, 2021).

Jonathan Gottschall, The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012), 11.

A lovely piece: thank you.

Apart from the loveliness, I learned, in particular, that the "harm or kill by shaking" meaning of "worry" long preceded the "feel anxious" meaning (I had assumed the opposite to be true), and that "bead" derives from "bede" meaning "prayer". Fascinating!