The construction “as best as” looks so glaringly wrong to me that I can’t help being mystified by the fact that I encounter it everywhere, not just in speech but also in published work. Here’s the error I’m talking about:

The writer of that sentence1 clearly meant “as best he could.”

To do something “as best one can” means (per Merriam-Webster) to do it “as well, skillfully, or accurately as” one can or, in British English, “as effectively as possible within one’s limitations.” CollinsDictionary says, “If someone does something as best they can, they do it as well as they can, although it is very difficult.” As in,

We should continue to resist fascism as best we can.

(That’s

, writing in The Bulwark.) Here’s another good example:Life doesn’t stop, and we’re riding it as best we can, but how can we keep from being jumpy now and then?

(That’s James Harbeck on the Sesquiotica blog, writing about the word desultory.)

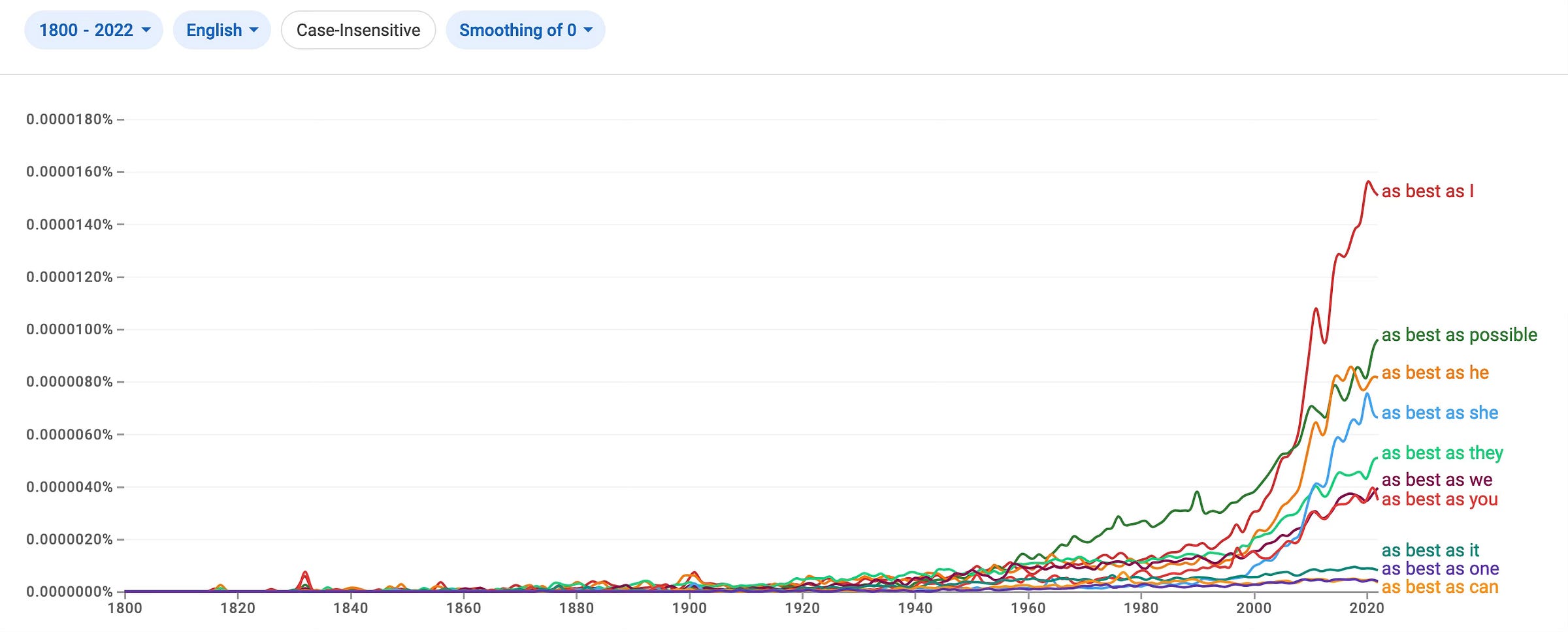

The phrase “as best,” used in this sense, has been around a long time. The earliest example I see in the OED is from 1480: “The said merchand sall sell his corne to fremen as best he may.” But unfortunately, this well-established, perfectly correct phrase seems to have picked up interference from another construction: the as–as comparison.

The human brain likes patterns

Our brains are very familiar with the as–as pattern (which has been in use since at least the early 1200s)—as soon as possible, as happy as a clam, As Good As It Gets. As a result, some brains insist on cramming the perfectly legitimate square “as best” peg into the more familiar round as–as hole.

Put another way, “as best” is apparently being misconstrued as a shortened form of “as best as.” If some speakers feel they are being “more correct” by supplying a second as, then the resulting grammatical error could be categorized as a hypercorrection. In any case, it’s ugly:

This nonsensical structure occurs frequently in speech—even in the speech of people who should know better. (I’m sorry to report that Barack Obama is a repeat offender, using this wrong construction not just in casual interviews but also in formal public addresses—e.g., here and here.) But it has become depressingly widespread in published sources too, even reputable ones.

Many grammar guides categorize the appalling “as best as” mashup as a “common error” in English. Other sources consider it merely “not standard” (ugh). At least one book on grammar, in an act of praising with faint damnation, calls it “highly informal.” (The author of an infuriating 2006 Chicago Tribune article, who manages to get wrong almost every aspect of this issue, comes to the hideous conclusion that “as best as” is “an acceptable alternative” to “as best.” No, no, no!)

Treating “as best” as a shortened form of “as best as” has two problems.

To infinity and beyond!

The first problem is (I hope) obvious: best is a superlative (as an adjective, it’s the superlative form of good; as an adverb, it’s the superlative form of well) and as such (ho-ho) “denotes an extreme or unsurpassed level or extent.” One thing simply cannot be more or less unsurpassed than (or as unsurpassed as) another thing.

I sometimes comfort myself with the thought that no one says “as worst as,” so we haven’t completely lost the ability to distinguish meaning from nonsense.2 I have also never seen a comparative adjective or adverb become entangled with the as–as pattern: no one would say “as better as it gets” (would they?).

Conjunction disjunction

The second problem with interpreting “as best” as an abbreviated as–as construction is that the as’s don’t match. That is to say, the as in the as–as structure doesn’t mean the same thing as the as in “as best.” (Note that the tiniest words in English are often the trickiest.)

In a comparison like “as cool as a cucumber,” as means “to the same degree or amount.” (The first as is an adverb; the second as is a correlative conjunction.)

But the as in “as best” (also a conjunction) means “in the way or manner that.” If you do something as best you can, you do it in the best way that you can.

Back in the ’80s, the writer

offered a list of observations that might be taken as evidence that things were generally getting worse. The one that stuck in my mind was that “Progresso artichoke hearts frequently have sharp, thistly pieces left on them now, as they never used to.”3Some things may indeed be getting worse. Is our ability to communicate with each other one of them? Widespread fuzziness about the meanings of common words like best and as doesn’t seem like a good sign. But at least there will always be plenty of sharp, thistly pieces of language for me to complain about.

Megyn Kelly, on her eponymous website (to which I will not link) on September 10, 2024, complaining about the unfair treatment of a certain Republican candidate by the presidential debate’s ABC News moderators.

But alas, a quick search of Google Books turns up plenty of occurrences of “as worst as,” though let’s hope most of them are cases of imperfect translation. (I don’t have the heart to check.)

Nicholson Baker, “Inner Space: Changes of Mind,” first published in The Atlantic (November 1982) and later collected in The Size of Thoughts: Essays and Other Lumber.